Русская версия Создано и (или) распространено. Дискриминационные аспекты применения законодательства об «иностранных агентах»

Introduction

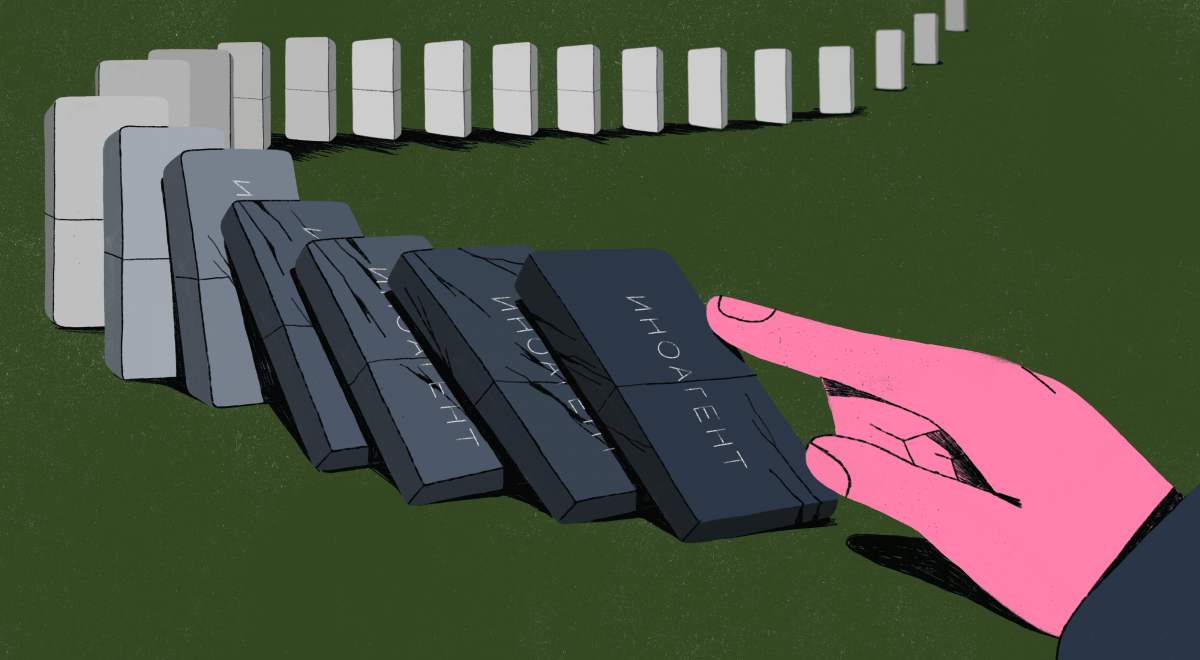

Spring-autumn of 2021 has already gone down in history as a series of ‘black Fridays’ — it is on Fridays that the Ministry of Justice most often updates the lists of so-called ‘foreign agents’. The black mark was given to the largest independent media, such as ‘Dozhd’ TV channel and international Russian-language media ‘Meduza’. The list has been replenished with dozens of individuals. The leading Russian NPOs, ‘International Memorial’ and the ‘Memorial’ Human Rights Centre, got under threat of closure: the prosecutor’s office demanded their liquidation due to ‘repeated violations of the legislation on foreign agents’. What was happening could not but cause a wide resonance, as a result of which a public consensus appeared — the legislation on foreign agents is frankly harmful to both society and the state, it must either be cancelled or significantly adjusted.

A sharp increase in law enforcement activity was preceded by the adoption of new amendments to the legislation on ‘foreign agents’ in November 2020 — March 2021. Amendments at the legislative level have significantly expanded the scope of application of legislation, tightened penalties and increased the regulatory burden on ‘foreign agents’. Since December 2020, 127 entities and individuals have been included in various lists, a total of 175 at the moment. In the first half of 2021, the courts of first instance imposed fines of 8.5 million rubles on NPOs and their directors in connection with violations of ‘foreign agency’ legislation.

Fines for violating the labelling of ‘foreign agents media’ have become massive: by October, Roskomnadzor reported on the compilation of 843 such protocols.

New amendments and established law enforcement practice significantly restrict, and sometimes completely stop the work of organisations and people included in the lists of ‘foreign agents’. 98 NPOs were forced to cease their activities after being included in the list of ‘foreign agents’, mass media and media projects are being closed (for example, VTimes and the ‘Fourth Sector’), other NPOs faced the risk of forced liquidation — the prosecutor’s office’s claims against Memorials are unequivocally read in the professional community as an unambiguous warning for all ‘foreign agents’. There has already been a trend towards a new wave of emigration of journalists and human rights defenders associated with the risks of a ‘foreign agent’ status.

The new campaign to regularly declare the media and journalists as ‘foreign agents’, which began with the inclusion of ‘Medusa’ in the list, disturbed the journalistic community, and the fact that popular media with millions of audiences got included in that list as well, took the topic beyond the limits of a narrow professional interest. And the attitude of society to the legislation itself and its use is quite unambiguous and negative: according to the poll of ‘Levada-centre’, 40% of respondents consider the law repressive. The petition for complete abolition of the ‘foreign agents’ law, following 240 organisations, including leading Russian media and charitable organisations, the largest civil and environmental projects from all parts of the country was signed by more than 250 thousand people.

The resonance and unambiguously negative perception of the law by both the professional community and society as a whole moves the situation into a political field. In addition to the already mentioned and most massive initiative for the complete abolition of this legislation, other ideas are emerging from various professional circles and political actors. A group of journalists headed by Dmitry Muratov, editor-in-chief of ‘Novaya Gazeta’, developed a package of amendments regarding the ‘foreign agents’ media. The bill on changing the legislation has already been developed in the State Duma by the fractions of ‘Spravedlivaya Rossiya’ and ‘Novyye Lyudi’ in the State Duma. The Human Rights Council under the President of the Russian Federation and the Union of Journalists of the Russian Federation have suggested their own versions of the amendments, the amendments are being developed in the Legislative Assembly of St. Petersburg. The expediency of considering and adopting such amendments has been repeatedly expressed by the press secretary of the President of Russia Dmitry Peskov. The President himself publicly confirmed this opinion in his speech at the Valdai Forum. The need for a detailed analysis of law enforcement practice and subsequent changes in legislation was also stated by the speaker of the Federation Council Valentina Matvienko.

If it were not for the continued activity of the law enforcement officers, who not only do not react to public and political discussion, but also tighten the sanctions applied, it would be possible to talk not just about public, but also public-state consensus. The only question that still causes controversy is how exactly it is necessary to change the legislation on ‘foreign agents’. Society and the professional community of NPOs and media insist on the complete abolition of legislation — it cannot be improved, it should be abolished. Representatives of the authorities, parliamentary parties and a number of other actors insist that it cannot be cancelled, it should be improved.

The choice between these two options lies, first of all, in the political perspective — is the government ready to listen to society? And if so, how and when? But this issue also has a legal dimension — to what extent do the laws themselves and the established law enforcement practice generally comply with the Russian Constitution and international law? Is there anything to improve there, and is it possible to change this legislation in such a way that the law becomes not just a document approved by officials, but also an indisputable part of the law?

Our report is dedicated to finding answers to these questions. Both sides appeal to discrimination to argue their positions. Supporters of the repeal emphasise that the legislation discriminates against NPOs and foreign agents (media and individuals). The authorities claim that the law increases transparency and does not restrict the rights of those who get into the relevant lists in any way. Therefore, in the report we focus specifically on identifying and analysing discriminatory aspects of the legislation and law enforcement practice itself. We hope that the movement of the dialogue between the government and society into the direction of legal analysis will allow us to find a solution that will simultaneously suit both sides, and will comply with the norms of the Constitution of Russia and international law.

Definition of discrimination in international and national law

According to the Constitution of the Russian Federation, the State shall guarantee the equality of rights and freedoms of man and citizen, regardless of sex, race, nationality, language, origin, property and official status, place of residence, religion, convictions, membership of public associations, and also of ‘other circumstances’. This provision complies with the norms of the Conventions ratified by the Russian Federation: the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

In general, discrimination is usually defined in international and national law and in judicial practice as unequal treatment in the lack of objective and reasonable justification, legitimate purpose, necessity and proportionality. Discrimination can be direct or indirect. Direct discrimination is characterised by the intention to discriminate against a person or a group, and indirect discrimination looks like an outwardly neutral position, criterion or practice that de-facto puts representatives of a certain group at a disadvantage compared to others. Discrimination has not only direct consequences for the people and groups who are subjected to it, but also indirect and profound consequences for society as a whole.

International treaties, like the Constitution of the Russian Federation, provide interference with fundamental human rights in several cases, including cases in the interests of national security and public order. This should happen only under strict conditions stipulated by law and the needs of a democratic society. At the same time, the state should demonstrate that the restriction is necessary to prevent a real, not just a hypothetical danger, and that less serious measures will not be sufficient. In addition to meeting immediate social needs, the restriction should also be proportionate to its purpose.

Finally, the Constitution prohibits passing laws abolishing or diminishing the rights and freedoms of man and citizen, and the interpretation of rights and freedoms as their rejection or derogation cannot be permissible.

What lists are there?

At the time of publication of this report, there are 4 lists of ‘foreign agents’. There is a separate regulatory regulation around each, separate procedures and different inclusion criteria. Below we will briefly describe each list, the criteria and the number of initiatives and people included in them.

Non-profit organisations

Since 2013 and until the publication of this report, 217 organisations have been included in the list of ‘NPOs performing the functions of a foreign agent’. 98 of them were excluded after liquidation or reorganisation, 39 were removed after filing an application for termination of foreign financing and (or) political activity, 5 were excluded after their complaints about the unjustified or illegal inclusion of the organisations in the list were upheld, and 1 of them was removed after returning property to a foreign source. 73 NGOs remain on this register. 73 NPOs remain in the list.

As reasons to include an organisation in this list, the law gives two separate criteria: ‘political activity’ and receipt of funds or property from foreign sources (including through intermediaries). The concept of ‘political activity’ is formulated very vaguely and tricky and covers activities that are not political in the general meaning of the word — for instance, elections observation, public appeals to the authorities, conducting polls or ‘spread of opinions about decisions taken by state bodies and the policy they pursue’.

Unregistered public associations

3 initiatives were included in the list of ‘unregistered public associations performing the functions of a foreign agent’ in 2021.

The same criteria are used for inclusion in this list as for the list of NPOs.

‘Foreign Media’

Since the end of 2020, 99 items have been added to the list of ‘foreign mass media performing the functions of a foreign agent’: 63 individuals, 27 legal entities of the media and 9 legal entities created by individuals at the request of legislation (individuals included in the list are required, according to the law, to register a legal entity and submit reports also on their behalf).

Despite the name of the list, not only foreign media and structures, including those without a legal entity, but also Russian legal entities and even individuals, including Russian citizens, can be put on it.

Unlike other lists, the criteria for inclusion in ‘foreign media’ are built around not ‘political activity’, but the spread and creation of materials. Thus, any foreign media or structure, when distributing materials on any topic and receiving foreign funds or property, can be included in the list of ‘foreign media-foreign agents’. Russian legal entities may be included there upon the fact of spread of materials belonging to the people already included in the list — in combination with funds and property of foreign origin or property received from people included in the list before. Any of the above criteria apply to individuals.

For example, working as a freelance author for a media already on the list may be the reason to be included there as well. Another reason can be a repost of any material in social media, regardless of the topic and the source — if the author of the repost receives foreign money or property.

Individuals

At the end of 2020, a law was passed implying the creation of another list exclusively for individuals. At the time of writing, no one has been included in this list yet. According to the law, people who are engaged in ‘political activities’, as well as purposeful collection of information in the military field, if this threatens the security of Russia can be put on the list. Along with foreign funds or property, the law introduces another category of assistance of foreign origin, which is the reason for including a person in the list: ‘organizational and methodological assistance’. This concept is not deciphered in any way, so it is impossible to understand in advance what types of relationships with people or organisations outside of Russia can lead to the status of a ‘foreign agent’.

How is the status assigned?

The law implies that organisations and individuals must themselves submit applications for inclusion in various lists of ‘foreign agents’ when registering or when intending to carry out the activities of a ‘foreign agent’. It applies to all lists except the list of ‘foreign media’. If an organisation or individual does not submit such an application, the Ministry of Justice may include them in the relevant list itself. At the same time, as a rule, an administrative case is initiated against the organisation and its official or individual.

NPOs may be subjected to an unscheduled inspection if citizens or organisations complain that they perform the functions of a foreign agent, but have not submitted an application for inclusion in the relevant list.

- So, in the spring of 2016, the Institute of Law and Public Policy provided the Ministry of Justice with copies of 47 types of documents on 11,867 sheets. According to Nataliya Sekretareva, the lawyer of the organisation, «three employees, including the executive director and the chief accountant, spent more than a week of working time. In total, the organisation lost not only a quarter of a month, but also almost 85 thousand rubles. The organisation’s expenses included the salary of employees who were separated from work, the cost of paper and toner for the printer. According to the results of the inspection, there were no signs of the Institute’s political activity. […] As it turned out later, the only reason for an unscheduled inspection was a citizen’s appeal of January 11, 2016. The organisation managed to get the text of the appeal only eight months after the request and three subsequent complaints. The appeal did not contain a request to conduct any checking, nor any information about the Institute’s political activities. During the subsequent trial, a representative of the Ministry of Justice stated: «[the citizen] does not give specific signs of [political activity]; if he knew about them, he would have given them, but he did not know. To do this, we checked you to find out if they exist or not.».

If an NPO is included in the list based on the results of such inspections, it happens by the decision of the Ministry of Justice, without any judicial procedure. Organisations and individuals often find out about it by chance from the media or from acquaintances. «I knew that I was labelled as a ‘foreign agent’ from a friend. He sent me a message with a link to the Ministry of Justice website and highlighted my name on the screenshot.» — says the coordinator of the ‘Voice’ movement in St. Petersburg. Her colleague from the Samara region also found out about it by accident: «No one called me, I did not receive any papers through the „Gosuslugi“ or through the mail.»

The specific grounds for inclusion in the list often come up much later, already during the appeal of the decision in court. This is how, for example, it became clear how widely the Ministry of Justice interprets the concept of a ‘foreign source’ of funds or property. The leading lawyer of the Center for the Protection of Media Rights Galina Arapova tells: «Objections to all claims look about the same: the Ministry of Justice, explaining the reasons for the inclusion of journalists in the list, points to the use of correspondent accounts for international money transfers, for example, through the correspondent account of Citibank Europe. At the same time, none of the journalists have their own accounts there, this bank is used by Russian banks as an intermediary.».

Among the possible grounds for inclusion in the list of ‘foreign agent media’ the Ministry of Justice named participation in a press tour, which was paid for by a foreign organisation; participation in an international conference with accommodation at the expense of the organiser; a monetary gift from friends or relatives living abroad; receiving an award for participation in an international competition. Despite the fact that this list of sources of ‘foreign financing’ raises questions, in practice, any transfers from foreign accounts, including their own, can become a reason for inclusion in the list. Three and a half months after being included in the list, journalist Pavel Manyakhin found out in court that the list of claims of the Ministry of Justice included three bank transfers in dollars, which, as Manyakhin told ‘Medusa’, were made by himself from one of his accounts to another.

Sergey Kurt-Adzhiev, editor-in-chief of ‘Gagarin Park’ media, says:

»… we allegedly received foreign funding from such organisations as the Togliatti Chamber of Commerce and Industry, Victoria LLC and the Union of Journalists of Russia. From the latter we had a grant for publications on a social topic. So, it was recognised as foreign funding because the Union of Journalists of Russia received funds from a certain organisation that received funds from a certain foreign source. That is, this is already a ‘second cousin’ of some kind».

Let’s assume that ‘foreign financing’ means only those funds from foreign sources that are related to professional activity, and not just a formal reason for inclusion in the list. But even in this case, it is completely unclear how a legal entity or an individual, not wanting to violate the law, can understand whether another person receives foreign funding. Such information cannot be obtained without access to bank secrecy. One of the journalists included in the list says:

In the report, we must list our expenses and sources of income. For example, who transferred money to me — with a first and last name. I also have to note whether this person receives money from ‘foreign persons’. If yes, you need to specify the number of his passport. How can I know about this if, for example, a friend returns money to me after I paid for the whole company in a cafe? And why should I even know about it?

Sergey Kurt-Adzhiev says:

«If a client appears and I make a contract with him, should I contact Rosfinmonitoring? „And please, tell me, has this client worked with any other clients who had foreign financing?“ And what will Rosfinmonitoring do? He’ll just tell me to go to hell. He will say that he is not obliged to provide us with such information. I will make this contract with the client, I will receive 10-15 thousand from him. Next year, the Samara Ministry of Justice will conduct an audit and will say that we received foreign funding again. No one can understand where this foreign financing ends.»

Under the current criteria of a ‘foreign agency’, any legal entity or individual is at risk of being included in the list, for example, as a result of provocation. As Denis Kamalyagin, the editor-in-chief of the ‘Pskovskaya Guberniya’, has shown, even officials can be easily compromised in this way:

»… I found the numbers of our governor, the head of the administration, the State Duma deputy from the Pskov region, the settlement account of two ‘anoshkas’ [‘Media60’ and ‘MediaCentre60’] publishing pro-government media. I sent them funds by phone numbers linked to their mobile banks— and in the latest report of the Ministry of Justice I reported that they received funding from a ‘foreign agent’ […] In theory, these comrades who will participate in the elections should indicate on at least 15% of their [advertising] area that they are associated with ‘foreign agents’.

The autonomous NPOs described by Kamalyagin could be included in the list of ‘foreign media of foreign agents’, however, the fact of the transfer of money by a ‘foreign agent’ does not always lead to the inclusion of its addressee in the list, even if the Ministry of Justice knows about it. In fact, the funds received from ‘foreign agents’ are only a formal opportunity to apply the law, which still works selectively.

In any case, recipients of donations or grants cannot protect themselves from the risk of becoming a ‘foreign agent’, even if they make an effort to do so and disown any foreign support. Considering different cases of the definition of ‘foreign agent’ in Russian legal practice, the experts of the Venice Commission note the ‘absence of a reasonable connection’ between this term and the practice that it is intended to reflect.

Problems with the breadth of definitions in the legislation are also shown by the fact that in October 2021, the Ministry of Finance proposed to exempt media established by state agencies or receiving subsidies from the state budget (such as RT or TASS) from the obligation to report to Roskomnadzor on foreign financing. According to the ministry, «attempts to influence the Russian information space from the outside in order to provide biased information and create a distorted picture of political reality can only take place in relation to commercial media that do not have state funding (subsidies) and priority goals and activities of such media established by state authorities.» That is, according to the logic of the ministry, a part of the media that may mistakenly fall under the criteria of a ‘foreign agent’ should be manually removed from the law. Oleg Matveichev, deputy Chairman of the State Duma Committee on Information Policy, noted in a comment to Vedomosti that «receiving any funds from abroad in these cases does not contradict the spirit of the law, the essence of which is that there should be no media that are subject to foreign influence through foreign financing.».

The authorities have repeatedly stressed that the status of a ‘foreign agent’ can be appealed in court.

- Alexander Sidyakin (State Duma deputy), 2013: «It seems to me that we can think about putting judicial practice on the letter of the law. The courts, in a sense, set the trend.»

- «If there are grounds to believe that one or another NPO has nothing to do with political activity, then it should be cited as a concrete example and challenged in court, » ‘Rossiyskaya Gazeta’ wrote in 2015 with reference to the presidential press secretary Dmitry Peskov— «Specifics are needed here, there is no need to feel abstract concern. And the problem is that most often there is an abstract concern that is not based on anything.».

- Valentina Matvienko (Speaker of the Federation Council), 2021: «Now the main thing is law enforcement practice, so that there are no excesses here. The Ministry of Justice carefully analyses everything before including an organisation in the list of foreign agents, this is confirmed by factual material, sources of foreign funding. But if one or another media does not agree with the decision of the Ministry of Justice, it has the opportunity to challenge it in court.»

However, appeal to court implies time and financial costs borne by public associations and individuals. According to experts' calculations carried out in 2015, the average expenses of an NPO for appealing fines in court or being put on the list were 75 thousand rubles. At the same time, for the entire time of the existence of legislation, we know only about four organisations that managed to get an exclusion from the list in court, and only in two cases it was a decision of the court of first instance. Thus, when new people or organisations get included in the lists of ‘foreign agents’, they face the question — is it worth it, to get distracted from work and invest effort and money in a long process, in which almost no one has managed to achieve justice?

Formal requirements for ‘foreign agents’: reporting

One of the most striking manifestations of inequality in relation to ‘foreign agents’ is the reporting burden, which is much lighter or completely absent for persons not included in the lists.

Reporting of legal entities

Most non-profit organizations (NPOs) are required to submit reports to the Ministry of Justice once a year on the purposes of spending money and using property, including those received from foreign sources. However, ‘foreign agents’ must do this once a quarter and additionally report on the goals, as well as on the actual expenditure of foreign funds and the use of foreign property. This applies not only to NPOs, but also to unregistered public associations (UPAs).

All NPOs are checked by the Ministry of Justice for compliance with the law and their constituent documents. For most organisations, it happens according to a preliminary plan and no more than once every three years. NPOs included in the list may be regularly checked by supervisory authorities once a year. NPOs that are not included in the list can also be checked unscheduled — based on a complaint from citizens or organisations, which claims that the organisation performs functions of a foreign agent, but has not submitted an application for inclusion in the relevant list. This practice contradicts the general recommendation of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the legal status of non-governmental organisations in Europe. According to this recommendation, unscheduled inspections of NPOs are possible only if there are sufficient grounds to believe that serious offences have been or will inevitably be committed.

NPOs included in the list should report more often than others — once every six months — on their activities and on the personal composition of their managers and employees (this report should be posted on the Internet or published in the media). Foreign agents NPOs, as well as structural subdivisions of foreign non-profit non-governmental organisations (NGOs), are required to conduct an audit once a year and submit an audit report to the Ministry of Justice. An independent assessment conducted in 2015 showed that these organisations incur an average of additional expenses in the amount of 273 thousand rubles per year. This estimate includes audit and regular reporting costs. However, according to the study, if an organisation was included in the list not on its own initiative, but by the decision of the Ministry of Justice, then a fine is added to these expenses, which on average amounts to 330 thousand rubles. If an NPO decides to challenge this fine, then it will spend an average of 75 thousand rubles more on court costs (payments to staff lawyers or third-party lawyers).

In 2021, non-profit organisations included in the list and subdivisions of foreign NGOs were obliged to inform the Ministry of Justice in advance about planned programs and events. And the Ministry has received the power to prohibit the implementation of a program or to hold an event. In case of non-execution of the decision, the Ministry of Justice may apply to the court with a request to liquidate the organisation.

The experts of the Venice Commission see a violation of the principle of legality in this law, that is, a clear definition of the norms of law and the boundaries of requirements. Although the law defines that the decision of the Ministry of Justice must be motivated, it does not establish any criteria for banning the program or allowing its implementation. It remains completely unclear what organisations should focus on when developing their programs in order to avoid the ban. It is also unclear how the court will be able to fulfill the goal assigned to it, namely, to assess the alleged misconduct and choose a sanction commensurate with this offense — since there are no criteria for an independent decision whether to satisfy the liquidation requirement.

Introducing this bill to the State Duma, the Government of the Russian Federation justified its necessity as the need «to protect the rights and freedoms of man and citizen, as well as the legally protected interests of society and the state.» It is worth noting that, according to international norms, only very serious violations, for example, threatening the fundamental principles of democracy, can serve as a justification for banning the activities of an organisation that is protected by freedom of association. It is obvious that even without innovations, the executive authorities had the authority to prohibit activities in exceptional cases. However, now the law presupposes systematic state interference in the content of the activities of ‘foreign agents’NPOs and subdivisions of foreign NGOs, making them directly dependent on the decisions of the Ministry of Justice.

Special attention should be paid to the projects of changing the reporting forms of non-profit organisations, which introduce more reporting requirements, and that automatically implies a sharp increase in the expenses of ‘foreign agents’ NPOs and subdivisions of foreign NGOs. In addition, the requirement to coordinate events for a year ahead will obviously lead to the impossibility of holding spontaneous events (for example, as a response to the events taking place in the world). The requirements to provide lists of participants of events (surname, first name and patronymic) and/or its counterparties — as well as the requirements for all NPOs and public associations to provide lists of citizens who have made donations to the organisation — force them to violate federal legislation ‘on personal data’, which prohibits disclosing and distributing personal data to third parties without the consent of the subject. The same requirements force to violate the right to privacy of participants of these events and private donors. As the Venice Commission notes in its report on the financing of associations, «such a radical measure as the ‘obligation to disclose information’ (for example, the disclosure of the source of funding and the identity of donors) can only be justified in cases where political parties and organisations officially participate in lobbying activities for a reward…»

Almost all of the above measures do not apply to all non-profit organisations (many of which also receive foreign funding), but create special conditions for ‘foreign agents’ and subdivisions of foreign NGOs. The regulatory framework distinguishes the participants of events and donors of such organisations into a separate category of people whose private life is not inviolable, and whose data does not need protection. All these are manifestations of direct discrimination.

A clear example of a special approach to ‘foreign agents’ was the decree of the Government of the Russian Federation No. 438 of April 3, 2020, made to support organisations during the spread of coronavirus infection. This decree introduced a temporary moratorium on most inspections for NPOs whose average number of employees in 2019 did not exceed 200 people. However, the moratorium does not apply to ‘NPOs performing the functions of a foreign agent.’

Reporting of individuals

The same reporting requirements apply to persons included in the list of ‘foreign mass media performing functions of a foreign agent’. In fact, once in this list, a person is equated with a ‘foreign agent NPO’, receiving its rights and obligations. Like all foreign entities, individuals are required to register a Russian legal entity within a month, submit an application for inclusion of this person in the list of ‘foreign agents media’ and send reports on its behalf in the form provided for NPOs. It is impossible to collect all the documentation and register an NPO in such a time, so people are forced to register commercial organisations and report on their behalf in the form of non-profit organisations. At the same time, the inevitable costs fall on their shoulders. For example, the state fee for the registration of an LLC is 4 thousand rubles, and for an annual audit — provided that there was no activity during the reporting year — it takes from 30 thousand rubles. If the activity was present, then audit costs rise sharply plus accounting costs are added to them. In addition, as some experts note, not every accountant or auditor today will want to deal with a ‘foreign agent’: »…The environment is considered toxic, problematic, and they try to stay away from it. And those who undertake the support of such NPOs, bill significantly higher than the market average».

Individuals included in the list of ‘foreign agents media’ are also obliged to report on their activities and financial activity, which leads to numerous violations of the right to privacy, says Daria Apakhonchich, included in the list:

They tell you: here’s a piece of paper and a pen, write down what kind of a spy you are… And how should one write it? What kind of socio-political activity do I do? I go for a walk with my children, eat, sleep, give lessons — what should I write there?

In terms of finances, nothing is clear either. After the search, all the equipment was seized from me (my and my daughter’s laptops, phones, my son’s tablet and memory cards). I made a post that I was collecting money for a new equipment, instead of the seized one. People donated a lot of money to me (more than 120 thousand). How do I know who these people are? What nationality are they, what passports do they have? I don’t know how to track it all technically.

The vagueness and breadth of the wording of the law and regulatory norms leads to numerous ambiguities that the Ministry of Justice does not clarify. At the same time, individuals are criminally liable for incorrect reporting with a potential imprisonment of up to five years. «We cannot predict that our reports will be recognised as a mistake, » says another ‘agent’ journalist who decided not to disclose her name — If I spent the cashback that comes every month from the bank, I have to report it. But it doesn’t seem to be necessary to specify each purchase separately in the report. Why? Because there is no explanation of how to fill out these forms. Some of the ‘foreign agents’ enter each chocolate bar and the receipt number, others combine product categories, for example, ‘groceries’, ‘transport’ and so on.

Lawyer Galina Arapova, specialising in the cases of ‘foreign agents media’, subsequently included in the same list, confirms this in an interview with ‘Novaya Gazeta’:

»…It is not clear what ‘actually incurred expenses’ are — is it necessary to collect all receipts, all transactions, each receipt for purchased underpants or coffee, or is it still about enlarged expenses?»

At the same time, according to Arapova, it is impossible to get any clarifications from the Ministry of Justice:

«If you look at the example of the communication of ‘Dozhd’’ TV channel with the Ministry of Justice and Roskomnadzor […], then this is a conversation between a mute and a deaf. „Dozhd’“ formulates a specific question: „Could you please tell me, in what time, for what period should we provide something?“ […] They repeat: „Read the law.“ It turns out that they either don’t know anything themselves, or they don’t have this position formulated somewhere up there. […] Therefore, we are forced to act on intuition in this situation.»

It is noteworthy that legal entities registered by individuals in the list must comply with the same reporting requirements as well as labelling) as individuals. It increases the degree of responsibility and the total amount of fines. The Ministry of Justice, commenting on the inclusion of these legal entities in the list, noted that ‘we are talking about these citizens’ conscientious fulfilment of the requirements of the law established for persons included in the list and aimed at increasing the information transparency of their activities.’ Maria Zheleznova, a journalist in the media list, told the BBC that «the point of these procedures is that the state has even more opportunities to punish ‘foreign agents’ if it wants, because the fines for legal entities are bigger.» Galina Arapova also agreed with her, noting that «the founders will have to answer for any violations committed by the LLC, even if there are no funds on its account.»

According to the ECHR, the process of collecting and storing data related to the private life of an individual is an interference with the right to privacy. In this case, we are talking about such details of a person’s personal life, interference in which, from the point of view of international norms, can only be justified by the need to prevent a real threat to a democratic society. Lyudmila Savitskaya tells:

I no longer have a private and personal life, because Comrade Major and the Ministry of Justice know literally everything about me, including the brand of tampons I use. I have to report on every purchase, even the smallest one, in detail. I have to file a report every quarter. The form takes 86 sheets, in which you describe in detail what you spent the money on: kefir, cat food.

Then I have to report on all receipts. My mother lives in the suburbs, she has no medicines, and she asks to order them from Pskov. Now mom has to make a request to the bank and issue a cash-flow order to confirm that she is transferring money to medicines, and not to finance Joe Biden.

It is noteworthy that the explanatory note to the law, in which the concept of ‘foreign agent media’ was first introduced, does not contain any motivation for such strict measures, with the exception of «improving the legal regulation of the spread of mass media by foreign mass media». During the consideration of the bill in the second reading, the chairman of the committee responsible for the draft mentioned that when making decisions on the inclusion of individuals in the list, «mirroring in relation to the impact on our media» is primary. An explanatory note to another bill, which put into effect another list of ‘foreign agents’ individuals (not media), motivates the need for the law by the fact that it «will increase the legality and transparency in the activities of […] private individuals supported from abroad who participate in political processes on the territory of the Russian Federation.»

As in the case of legal entities, we are talking about the transfer of not only personal information, but also information about other persons, that is, a violation of the law ‘on personal data’:

«I’m also worried about my loved ones who transferred money to me — now I have to indicate them in the report. In our country, you never know how this information can be used. Will they want to put pressure on me through them if I somehow behave incorrectly, in the opinion of the state?» — argues the author of an anonymous essay on ‘foreign agency’, published in ‘Medusa’.

Thus, no specific justifications or explanations were given as to how ‘foreign agency’ laws should protect the interests of society and the state, how they will counteract threats to national security or prevent them. The Venice Commission, in its analysis of changes in the legislation on ‘foreign agents’, comes to the conclusion that the expansion of regulation is unnecessarily burdensome to such an extent that it becomes repressive. At the same time, numerous difficulties associated with the reporting of individuals included in the register of ‘foreign agents’ are confirmed by the testimonies of the ‘agents’ themselves. As Galina Arapova notes,»… the state goes beyond the boundaries of normal relations with its citizens. This report is a blatant invasion of a person’s privacy, not justified by necessity. It seems that such unpleasant, intractable bureaucratic difficulties are created in order for a person to feel how his dignity is being humiliated.»

Formal requirements for ‘foreign agents’: labelling

Another example of how the legislation on ‘foreign agents’ discriminates against the status carriers is the need for labelling. Thus, the media recognised as ‘foreign agents’ must accompany all their messages both on the website and in social networks with a special wording — a warning that the message was spread by a ‘foreign agent». In addition, an indication that the media performs the functions of a ‘foreign agent’ should be in the output data or on the publication’s website.

Special wording must be added not only to the texts of the ‘foreign agents’ media, but also to the video or audio materials. In each case, there are rules for the placement of such markings: if we are talking about the text, the size of the warning must be twice the size of the rest of the material. In the case of video, it should occupy at least 20% of the image on the screen and have a duration of at least 15 seconds. Similar duration requirements apply to audio materials.

The same rules apply to individuals included in the list of ‘foreign agents’ media. People from the list of ‘foreign agents-individuals’ are also required to mark their appeals to authorities or educational organisations.

Lyudmila Savitskaya: «Those media that traditionally loudly express contempt for the existing political system, expose corrupt officials, or are not afraid to joke about the president and the special services, their sons-in-law and daughters, have turned away from me, a newly minted foreign agent. They did not want to put a foreign agent postscript in front of my texts. They pretentiously stated that they were not accepting the law on ‘foreign agents’, added that the marking spoils the appearance of news and texts and summarised: „The management opposed such attributions in the materials on the site.“ It is important to make a note here that for the absence of a foreign agent mark, not the media will be fined, but me. First, I will receive a fine with several zeros, and if repeated, a real arrest. In prison, it will be difficult for me to help people with reports, and my lawyers and I decided that we would act according to the law: put a postscript, write reports and simultaneously challenge the foreign agency status. Therefore, the refusal to label my texts is a powerful betrayal from those with whom I have been cooperating for a long time.»

NPOs and unregistered public associations labelled as ‘foreign agents’, as well as their founders, members, participants and managers are required to indicate their status on the website and in social networks if their posts can be interpreted as ‘political activity’, as well as mark all materials produced by them and appeals to state agencies, local governments, educational or other organisations.

One of the discriminatory consequences of the law is, for example, the impossibility for ‘foreign agents’ to use Twitter: the maximum length of the message there are 280 symbols, and the length of the ‘foreign agent’ label is 220 characters. There are only 60 characters left for a post.

As a human rights activist Lev Ponomarev notes, ‘when they say that a ‘foreign agent’ in Russia has the same rights as other citizens, it is not true, of course. Take Twitter, for example: I am deprived of the opportunity to use it.’.

At the same time, the law on ‘foreign agents’ contains vague formulations that do not give a clear explanation of how to label your messages in each of the social networks specifically. In some cases, organisations were fined even after a previous check found no violations on the site.

«The main problem <…>, as it seems to me, is also that most of the questions <…> even lawyers cannot answer unequivocally — the wording in the law is so vague. For example, it is not clear how to put a label on Twitter. Most likely, you can use the picture to have the opportunity to write a tweet, but some lawyers do not agree with this. As a result, it is not clear how to use Twitter, » says Daniil Sotnikov, a journalist of the ‘Dozhd’’ TV channel.

At a round table devoted to the problems of ‘foreign agents’, Dmitry Treshchanin, the editor of ‘Mediazona’ said that labelling is a ‘minefield’. According to him, Mediazona writes about 350 messages a day, which are issued according to a certain template. The staff may think that they follow all the labelling rules, but in fact they don’t know if this is the right template. As a result, it is possible that the media commits about 350 violations a day without suspecting it, and it can find out about it only after violations are detected by Roskomnadzor, which threatens with a fine for non-compliance with the legislation on ‘foreign agents’.

Labels about ‘foreign agency’ scare away not only potential employers, but also media readers, and even ordinary users. At the same time, for people included in the list of ‘foreign agents’ it is necessary to indicate their status constantly in order not to receive fines for non-compliance with legislation. «If I place an ad for a sale of a wardrobe, I will also need to mark this message there. If I am going to write a thesis in some university in Russian, then I should also write this note there, if I am registered in a dating app– I will have to mark my profile, » notes Lisa Surnacheva, editor of the ‘Nastoyascheye Vremya’ TV channel.

It is necessary for ‘foreign agents’ to label messages even in more personal communication formats — for example, in dating apps or in parental chats. In the marathon of «Dozhd’» «Agents of people. Marathon for the abolition of laws on ‘foreign agents’’ the head of the ‘Center for the Protection of Media Rights’ Galina Arapova noted that such labelling significantly affects the private communication of people who have the status of a ‘foreign agent’. Even when submitting a request to enrol a child in school, a person is obliged to mark his application, which cannot but influence the decision of the facility administration. ’And when accepting the child, the director will think three more times whether he needs this headache’ the lawyer added.

In addition, the private life of individuals of the ‘foreign agents’ media is also affected by the fact that even ordinary users of social networks are beginning to label them, although the legislation does not require this. Such labels can be seen both in posts concerning individuals, as well as NPOs or the media. Apparently, such users decide to put labels based on the vagueness of existing legislation and out of fear that they themselves will be responsible for ‘violations’. Here, for example, is a comment left by a Twitter user telling which TV channels he watches: «<…> i’m also watching news of d*zhd (recognised as a foreign agent on the territory of the rf — should I write this at all?)».

Such an attitude to the status of a ‘foreign agent’, together with labels even from ordinary users, entails serious reputational costs for those who are included in the lists, and leads to discrimination.

NPOs and the media of this status are particularly exposed to such risks. The situation with information aggregators deserves special attention.In October 2021, the telegram channel ‘Setevyye Svobody’ noticed that the ‘Yandex.News’ aggregator began to label news as news from the ‘foreign agents’ media independently — Although there was no information that labelling affects the issuance of such publications, such a label cannot but affect the attitude of the audience: when searching for a particular topic, they may prefer the media without this label. Moreover, we are talking not only about those users who will choose a source of information without foreign funding, but also about those who will make such a choice simply without being informed about what such labelling means. As for NPOs, even without formal restrictions on receiving a grant, the proposed wording cannot but influence the decision of the grantee. The same restrictions apply to potential partners who may not want to cooperate with a ‘foreign agent’.

The historical meaning of the ‘foreign agent’, together with the need for labelling, leads to inequality of the parties in other cases: for example, when defending theses at a state university, if one of them is written by a ‘foreign agent’, or during a court hearing, if one of the parties is a ‘foreign agent’: «as far as I understand, now I will have to label all my procedural documents as a lawyer with this 24-word phrase, » lawyer Valeria Vetoshkina told ‘Advokatskaya Ulitsa’.

The need to label all their public messages in social networks also affects the quality of life of those whom the Ministry of Justice considered ‘foreign agents’. As the former journalist of the «Project» Olga Churakova notes: «The label is discrimination in personal life. Interference in your personal life. Lack of privacy. The authorities are constantly monitoring your personal life.»

Formally, the need for labeling is not related to discrimination against ‘foreign agents’, but only creates inconveniences for them. However, in reality, it not only restricts the rights to use certain social networks, for example, Twitter, but, as stated by the representative of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Liz Throssell, and violates the right to freedom of expression.

Sanctions for violations of requirements for ‘foreign agents’

In 2012, two articles were added to the Code of Administrative Offences with penalties for violations of the requirements of the legislation on ‘foreign agents’, and an article on ‘malicious evasion’ was added to the Criminal Code. With the increase in the number of types of ‘foreign agents’, the number and amount of articles increased, and sanctions for violations and the ‘statute of limitations’ on them grew. By the end of 2021, there are at least five ‘profile’ administrative articles with penalties for ‘foreign agents’, and the number of parts in the criminal article has tripled.

- According to the ‘Memorial’, in connection with various projects of the organisation, the courts imposed fines in the amount of 6.1 million rubles. In each case, Roskomnadzor issued two protocols: for the organisation (‘International Memorial’ or Human Rights Center ‘Memorial’) and for their officials (Yan Rachinsky and Alexander Cherkasov). In most cases, the court of second instance rejected the appeals.

According to the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, for four and a half years, from the beginning of 2017 to the middle of 2021, the courts of first instance considered 229 cases against NPOs on non-inclusion in the list or violation of the rules on labelling (under Article 19.34 of the Administrative Code) and issued 158 indictments (114 of them — on legal entities, 43 — on officials), imposing fines totalling 36,245,500 rubles. The average fine increased from 190 thousand rubles in 2017 to 350 thousand rubles in the first half of 2021. Some of the fines imposed in the first instance were appealed: the amount of fines under the resolutions that entered into force amounted to about 25.5 million rubles. Fines of more than 11 million rubles were collected forcibly.

Protocols for refusal to register in the list of ‘foreign agents NPOs’ were issued, in particular, to the following organisations: Information and Analytical Center «Sova», «Dynasty» Foundation, «Women of the Don» Foundation, Glasnost Defence Fund, «Institute of Globalisation and Social Movements», Kaliningrad Regional Public Institution «Society of German Culture and Russian Germans «Eintracht Consent», Krasnoyarsk regional public organisation «We are against AIDS», Murmansk regional organisation «Kolsky Ecological Center».

The Golos movement, the Public Verdict Foundation, Samara’s media Gagarin Park (registered as an NPO), Kaliningrad’s organisation ‘Ecozaschita! -women’s council’ and many other organisations were accused of the absence of labelling.

Organisations were fined due to the lack of labelling in publications on websites, posts on social networks, on books, handouts, banners at public events, appeals to government agencies and even on a board game on Soviet history.

- In December 2020, the court decided to fine the ‘International Memorial’ 500 thousand rubles, and its head — 300 thousand rubles for the lack of marking on materials at the ‘Memorial’ stand at the Moscow International Book Fair. The court ignored that the prosecutor’s check was carried out in violation of the law, the books were published before the organisation was included in the list of ‘foreign agents’, and before handing them over to fair visitors, the books were stamped with the label that the ‘Memorial’ is in the list.

- In October 2021, the ‘Memorial’ Human Rights Center was fined 300 thousand due to the lack of marking in an appeal sent to the electronic reception of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs by the head of one of the programs. In the document, several human rights organisations called on the Russian authorities to grant political asylum to the Turkmen blogger Rozgeldy Cheliev, who was persecuted in his homeland due to his posts on the Internet.

- In December 2015, a court in Tomsk fined 400 thousand rubles to the ‘GOLOS-Ural’ civil society development fund for the fact that during the presentation ‘What an election observer needs to do’, the observer’s mascot, the short-term observer’s handbook and the public controller in the PEC notebook were distributed without marking.

- Yekaterinburg’s ‘Memorial’ Society was fined 300 thousand rubles in 2020 due to the lack of labels on banners and information stands at a public event dedicated to the memory of victims of political repression. Yekaterinburg’s ‘Memorial’ was not the organiser of the event, nor the owner of the banners, and the logo depicted on them belonged to the entire ‘Memorial’ movement

Fines to organisations were even issued for the activities of other legal entities:

- In 2015, the court fined the ‘Memorial’ Human Rights Center 600,000 rubles for the absence of labels on two materials on the website of the ‘International Memorial’ Society.

- In 2016, the court fined the private institution ‘Information Agency ‘MEMO.RU’’ by 500 thousand rubles due to the lack of marking in the materials on the website of the ‘Caucasian Knot’. At the same time, the defender stressed that the founder of the publication is another organisation — MEMO LLC. The court found that this information «cannot be taken into account, since the head of both organisations is G.S. Shvedov, the activities of the organisations are based on a common interest.»

In October 2021, Roskomnadzor reported that since the beginning of the year they had compiled 843 protocols on violations of labelling from the ‘foreign agents’ media’s side (according to Article 19.34.1 of the Administrative Code). Of these, 840 were sent to ‘Radio Svoboda’ and to Andrey Shary, the head of the Russian service of media corporation, two protocols were sent to PASMI LLC (‘The First Anti-Corruption Media’) and its CEO Dmitry Verbitsky, and one to Lev Ponomarev, who was included in the list of ‘foreign agents’ media.

- By the end of May 2021, the amount of fines for labeling violations imposed on ‘Radio Svoboda’ exceeded 100 million rubles. On May 14, ‘Radio Svoboda’s’ Moscow bank accounts were blocked. Bailiffs visited the Moscow office of the media at least twice a month and took photographs of furniture and equipment. The media stressed that it would appeal against all fines, but by that time the court had dismissed all of the 140 appeals filed.

- The case of Lev Ponomarev was connected with the lack of labelling, in particular, when reposting other people’s Facebook posts. «When I write articles— I always indicate that the article was written by a foreign agent media, but when I repost— I just click on the button—» Ponomarev said in a conversation with RBC. — And why write that the repost was made by a foreign agent — I have no idea. I need to write that the repost was made by a foreign agent media at every repost.’ In November, the court of first instance issued an indictment and imposed a fine of ten thousand rubles — as RBC writes, it was the first fine against an individual for not labelling himself a ‘foreign agent’.

For a foreign media or a «Russian legal entity established by it», the consequence of an administrative case from 2019 may be not only a fine, but also the ban of the site by Roskomnadzor. Access is restored after the «confirmation of the fact of elimination of the violation that served as the basis for the ruling.»

- On November 17, 2021, Roskomnadzor, having drawn up a protocol for The Insider media due to the lack of labelling, recalled the possibility of restricting access to the site after the court decision comes into force.

For «repeated», «multiple», «gross» and «malicious» violations, in some cases, sanctions increase significantly, up to criminal liability and imprisonment. Under which violations the risks for repeated violations increase depends on the «foreign agent’ type. For organisations and people recognised as «foreign agents media», any violations, including those related to labeling requirements, are taken into account, for other types of «foreign agents» — only evasion from being included in the list and violations of reporting requirements.

- For «malicious evasion» of providing documents required for inclusion in the list of «foreign agents NPOs» or «foreign agents unregistered associations», a penalty of up to two years in prison is given (Part 1 of Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code). According to the official statistics, four people have been convicted under this article since 2015, but it is unknown what kind of cases they are, and it cannot be ruled out that cases from a neighbouring article on «arbitrariness» (Part 1 of Article 330 of the Criminal Code) have been included. It is publicly known about one criminal case of «malicious evasion» initiated in 2016 against Valentina Cherevatenko, the chairwoman of the «Women of the Don» Union. The office of the organisation was searched and equipment and documents belonging to the organisation were confiscated. According to investigators, Cherevatenko, creating the fund, deliberately did not apply for the inclusion of the organisation in the list of «foreign agents». A year later, the Investigative Committee dismissed the case for lack of corpus delicti.

- The penalty for individuals’ failure to submit an application for inclusion in the list after being brought to administrative responsibility for that is up to five years in prison (Part 3 of Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code).

- For the media, fines increase for any repeated violation (Part 2 of Article 19.34.1 of the Administrative Code). And for multiple violations, a fine of 5 million rubles is provided for legal entities (Part 3 of Article 19.34.1 of the Administrative Code), for citizens it’s criminal liability with a penalty of up to two years in prison (part 2 of Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code). From January to October 2021, Roskomnadzor compiled 420 protocols on repeated violations due to the lack of labelling of the media as a «foreign agent» and 30 protocols on gross violations (respectively, Part 2 and Part 3 of Article 19.34.1 of the Administrative Code).

In the summer of 2021, answering a question about the threat of criminal cases for journalists from the «foreign agents» media, presidential press secretary Dmitry Peskov said that this would not happen «if one strictly follows the letter of the law.» However, it is hardly possible to follow it because of the uncertainty of the requirements for violation of which punishment is provided. The decision on their interpretation remains with the law enforcement officer.

- Ivan Kolpakov (Medusa): «Just as the Ministry of Justice decided to include us in the list of „foreign agents“, the Ministry of Justice can behave in the same way with our reporting, exactly as they please. If they want to find errors in our reporting, they will find them. If they find mistakes, the fines will follow. If there are fines, it will mean criminal liability, for example, for me.».

- Lev Ponomarev: «Even reposts need to be accompanied by a label — well, this is complete nonsense. I’m probably going to stop doing reposting now. And I will only write more meaningful posts instead of reposts: they stimulate me to work. I will not deliberately run into a criminal case, but if they open it, then this is fate.»

A clear barrier creates a complex regulation: a large number of disparate articles and their parts with confusing formulations and not specific concepts, which, moreover, are being changed and supplemented.

- Three administrative articles prescribe penalties for NPOs, unregistered associations and individuals «performing the functions of a foreign agent» for failing to provide, late or not in full «information, the submission of which is provided by law and is necessary for the authorized body to carry out its legitimate activities to the authorized body». It is not clear from this wording what kind of information is meant — whether we are talking here about reporting of any sort or, for example, about an application for inclusion in the list. This ambiguity is especially critical for ‘foreign agents’ individuals: for them, repeated violation can lead to criminal liability.

- The law does not define what is considered «malicious» evasion — this concept is operated by the criminal Article 330.1 of the Criminal Code. Back in 2012, the Supreme Court criticised this wording, in its response to the bill it was noted that «the absence of a legally fixed definition of malice may cause difficulties for the law enforcement officer in assessing the objective side of the act in question and the degree of its public danger.»

- For people and organisations labelled as the «foreign agents» media, different types of violations are not separated, as a result of which the violation may become «repeated» even if it actually differs from the previous one.

- The number of protocols and, as a result, fines and repeated violations depends not so much on the actions of the «foreign agent» as on the authorities that make up the protocols: you can issue one protocol on the absence of labelling in several publications (as, for example, in the case of Ponomarev) or according to the protocol for each publication separately (as, for example, it happens with the ‘Memorial’ or ‘Radio Svoboda’).

All this, combined with the risk of severe sanctions, exerts psychological pressure on those who have already been included in the lists of «foreign agents», and cannot but have a deterrent effect for the industry as a whole.

- Darya Apakhonchich «Psychological discomfort is added to this illegal waste of time, because they adopted an amendment that criminalises non-compliance with all these requirements. It has never been used yet, but all the people who are now in this „waiting line“ are thinking: „So, won’t this be applied to me? Why do we need an amendment if it’s not used? They’ll probably be interested in trying it once.“ How ready am I for the fact that I will send an incorrect report now, and then they will put me in jail for it? It’s a terrible feeling that you don’t control anything and nothing depends on you anymore. They will do what they want.»

If individuals are afraid of a criminal case and imprisonment, some organisations may face closure. In addition to the blocking of accounts by bailiffs and the ban of websites by Roskomnadzor, in case of multiple violations, the authorities use administrative cases as a basis for applying to the court with a request for liquidation of an organisation.

- In November 2021, the Prosecutor General’s Office filed a lawsuit with the Supreme Court to liquidate the ‘International Memorial’, and the Moscow Prosecutor’s Office filed a lawsuit with the Moscow City Court to liquidate the Memorial Human Rights Center. One of the grounds was that, according to the prosecutor’s office’s lawsuit, the Memorial Human Rights Center «systematically concealed information about performing functions of a foreign agent.» Similarly, according to the Prosecutor General’s Office, the fact that International Memorial and its head have repeatedly been brought to administrative responsibility for violating labelling requirements, «indicates that the Company demonstrates sustained disregard for the law in its activities, does not ensure the publicity of its activities, prevents proper public control over it, which grossly violates human rights, including the right to reliable information about its activities.» Although the prosecutor’s office speaks of «systematic violations» of labelling requirements, most of the protocols were drawn up in a short period of time in autumn of 2019 and before the authorities explained that it was necessary to label not only the organisation’s website, but also websites of separated projects and posts on social networks. At the time of writing, the courts had not yet considered these claims.

What are the formal restrictions for «foreign agents»?

The authors and supporters of the laws on «foreign agents» have repeatedly stressed that we are talking about greater transparency of the activities of NPOs and media receiving foreign funding, and not about banning or restricting their activities.

«This law does not prohibit anything, this law is not prohibitive. It does not prohibit anything—» Vladimir Putin stressed during the discussion of the creation of legislation on «foreign agents» in 2012. —Its goal is to make this activity, especially the financing of those organisations that are engaged in political activities on the territory of the Russian Federation, transparent.»

From the statements of deputies and officials in on the «foreign agents» laws:

- Vladimir Burmatov (The State Duma deputy, ‘Edinaya Rossiya’ fraction), 2012: «I believe that this will make the political process more open and honest, and in no way infringe on the interests of political and public organisations operating in Russia, since it does not restrict their activities in any way.»

- Dmitry Peskov (press secretary of the President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin), 2015: «Whether an NPO is a foreign agent or not, does not change anything at all. Nothing prevents NPOs from acting and working further in the same mode.»

- Vasily Piskarev (The State Duma deputy, ‘Edinaya Rossiya’ fraction), 2020: «The „foreign agent“ label itself does not prevent a person or a public organisation from engaging in political activity, it does not prevent them from engaging in elections, demonstrations, organising mass marches — all of that is allowed, it is only necessary to label that it is done with foreign money. Let the people know who is calling for rallies, demonstrations and other political actions of all kinds.»

- Shkhagoshev Adalbi (The State Duma deputy, ‘Edinaya Rossiya’ fraction), 2020: «I can say that the bill we are currently adopting is a delicate, non-aggressive defense, because this bill categorically prohibits nothing, it just says: if you are engaged in political activity, register, tell about it and criticise the government if you want, or, on the contrary, support the system of power, you can do it.»

Despite the statements, the activities of «foreign agents» are significantly limited in various areas at the legislative level.

Electoral restrictions

All categories of «foreign agents» are prohibited from participating in campaigning for or against the nomination of candidates or otherwise participating in election campaigns and referendums. According to experts of the Venice Commission, this norm represents a disproportionate interference with freedom of expression, and due to practical difficulties in distinguishing between raising awareness and campaigning, it actually prohibits media included in the list of «foreign media» to cover elections. In order to understand this issue, special clarifications of the Central Election Commission were required, which once again underlines the uncertainty of the legislation. As a result, the CEC allowed «foreign agents media» to cover the elections,

Various electoral restrictions are also introduced by regulations at the regional and municipal level. In 2018, when the concept of «foreign agent» was still applied only to non-profit organisations, the Public Verdict Foundation found 314 documents with such restrictions being in force in 80 regions of Russia. In some cases, NPOs «performing the functions of a foreign agent» were prohibited from making donations to candidates’ election funds, in others — they were prohibited to put forward the initiative of holding a local referendum, to promote the nomination or election of deputies, to achieve a certain result in elections or otherwise «participate in election campaigns.»

The electoral legislation also introduces the concept of «affiliation» with a foreign agent using expanded criteria. Thus, any candidate’s connection with «foreign agents» is indicated for two years before the election is scheduled and during the election campaign: whether it is an institution, joining government bodies, working within an organisation or receiving financial or property assistance for «political activity».

For such candidates, as well as for the «foreign agents» themselves, special restrictions are introduced:

- to indicate their status in the donation payment document to the electoral fund

- to indicate information about their connections with «foreign agents» in the application for consent to run, in the subscription lists (next to the records of the previous criminal record) and in campaign materials (at least 15% of the material’s area)

- information about the status of such candidates should be on information stands in the premises of precinct election commissions. It should be indicated in the voting ballots as well.

Taking into account the results of opinion polls, which demonstrate the negative associations of the majority of respondents with the «foreign agent» term, it becomes obvious that serious discriminatory restrictions have been built up by the legislation for electoral associations as well. Thus, the party or movement nominating such a candidate must tell in any of its campaign materials and subscription lists that the association has nominated a candidate (s) from among «foreign agents» or people «affiliated» with them. According to the law, at least 15% of the material’s area should be allocated for this, or it should be clearly distinguishable by ear.

It is clear that parties are not interested in talking about their connection with something, that, according to research, almost half of the population associates with espionage.

In November 2021, it became known that the Central Election Commission ordered the development of an automatic registration system for «foreign agents» candidates, which will monitor the presence of mandatory labelling in campaign materials. Its cost exceeded 13 million rubles.

Limitation of state support for NPOs

In 2017, responding to questions from the European Court of Human Rights in connection with complaints about the «foreign agents»» law, Russian authorities stressed that the law does not restrict the financing of NPOs labelled as «foreign agents», since they receive presidential grants. In practice, the status of a «foreign agent» prevents the receipt of state financing. «Organisation is not included in the list of non-profit organisations performing the functions of a foreign agent, » such a phrase is often in the requirements for participants in tenders for the provision of certain subsidies. Here are just two examples of such contests:

- Subsidies from the Ministry of Education for carrying out patriotic activities with participation of children and youth within the framework of the «Patriotic education of citizens of the Russian Federation’ federal project (2021).

- Competition of the Ministry of Education and Science for NPOs performing the functions of infrastructure centres on financing programs of the development of the National Technology Initiative areas (2018).

Since 2016, the status of NPOs -"performers of useful services» — has been normatively fixed — these are socially oriented NPOs (SO NPOs), which, after registration in this list, are entitled to «priority support measures», including subsidies from the budget. To do this, an NPO must meet a number of requirements, in particular, only NPOs that «do not perform the functions of a foreign agent» can be «performers of useful services». If an organisation is labelled as a «foreign agent», it is excluded from the list of «performers of useful services». In some regions, the inclusion of SO NPOs in the list of foreign agents is even considered as macroeconomic risks in the implementation of programs for the development of civil society.

Sometimes this restriction is prescribed in the very conditions of regional and municipal competitions. We found such a requirement in regional competitions for socially oriented NPOs or a broader list of organisations that were announced in 2021 in Primorsky Krai, Yakutia, Rostov region, Khabarovsk krai. Grants were issued in the areas of civic and patriotic education, development of civil society institutions, environmental and animal protection, strengthening of interethnic ties, development of spiritual and moral foundations and traditional way of life, social protection of citizens, support of motherhood and childhood, prevention of drug use, support of young professionals, support of projects in the field of science, education and enlightenment, development of journalism and blogging, development of human rights protection and others. In 2020, NPOs from the list of «foreign agents» could not participate in the competition for regional subsidies for the organisation and conduct preventive measures among high-risk groups, vulnerable and especially vulnerable to HIV infection groups of the population of the Irkutsk region. Restrictions on state financing for «foreign agents» were indicated in the conditions of tenders for subsidies for the Novokuznetsk — Forge of Public Initiatives (2019), in municipal grants for anti-corruption, environmental protection, educational, patriotic and other projects in Simferopol (2016), Rostov-on-Don, Tula. Numerous restrictions on grants and subsidies for NPOs at the regional and municipal level were collected and published by the Public Verdict Foundation in 2018.

In addition to limiting funding from the budget, since 2020, bank deposits of NPOs from the list of «foreign agents» are not subject to insurance.

Restriction of control over the actions of the authorities

Federal law prohibits NPOs listed in the list of «foreign agents» from nominating candidates to public supervisory commissions. In December 2020, at a meeting of the Human Rights Council, Vladimir Putin devoted special attention to this issue, saying that he «cannot imagine that foreign agents in the United States would come and demand that they should be allowed into the public council of the State Department.»

Following the same logic, the Ministry of Health banned NPOs from the list of «foreign agents» from nominating candidates to the «Council of Public Organisations for the Protection of Patients' Rights» operating under the Ministry.

Additional restrictions are introduced by regulations and at the municipal level. NPOs «performing the functions of a foreign agent» are prohibited from nominating candidates to local Public chambers (for example, in Tyumen, Tobolsk, Norilsk), Public councils (for example, in Vladikavkaz).

- «Two weeks after the organisation was declared a foreign agent, local newspapers published information that Oksana Prishchepova was expelled from the Socio-Political Council under the governor. Later, the governor adopted a resolution to amend the charter of the council stating that a foreign agent does not have the right to be its member, » says the compilation of the NPO Lawyers Club about the Kaliningrad organisation «Woman’s World».

Since 2018, non-profit organisations «performing the functions of a foreign agent» are prohibited from conducting independent anti-corruption expertise of regulatory legal acts or their projects.

- Transparency International Russia, which was included in the list of «foreign agents» in 2015, appealed to the court against the ban on accreditation as anti-corruption experts in 2019. The law «discriminates against Transparency on the basis of being included in the list: of all non-governmental organisations, only our organisation systematically conducted an anti-corruption examination of RLAs, » the organisation said.

The legislation on «foreign agents» also restricted the work of election observers. Due to the declaring of election observation as «political activity», the organisations conducting the observation immediately found themselves in danger of being included in the list of «foreign agents». Since 2012, 10 organisations and 20 individuals engaged in the protection of electoral rights have been included in the lists of «foreign agents».

In 2014, the CEC stated that the observation of elections by representatives of NPOs labelled as «foreign agents» «could lead to discrediting the institution of observers, as well as creating conditions for destabilising the democratic process of forming public authorities.» Although in 2021, the head of the CEC, Ella Pamfilova, announced that Russian citizens participating in the activities of «foreign agents» organisations could be election observers, the legislative restriction on participation in election campaigns for «foreign agents» repeatedly called into question the possibility of observers associated with such a status. In June 2021, the Public Chamber banned the media and NPOs recognized as «foreign agents» from suggesting candidates for observers from the Public Chamber in the elections to the State Duma, the bodies of subjects and local self-government.

Other restrictions

The introduction of the concept of «foreign agent» into the legislation led to its introduction into more and more new laws, which led to the emergence of new restrictions in a variety of areas.